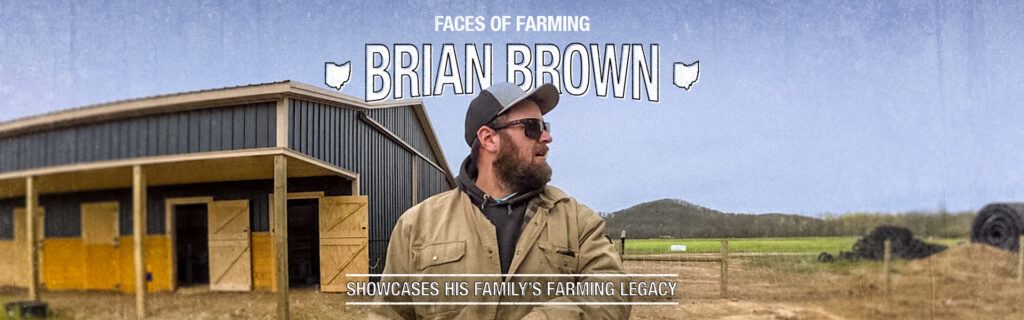

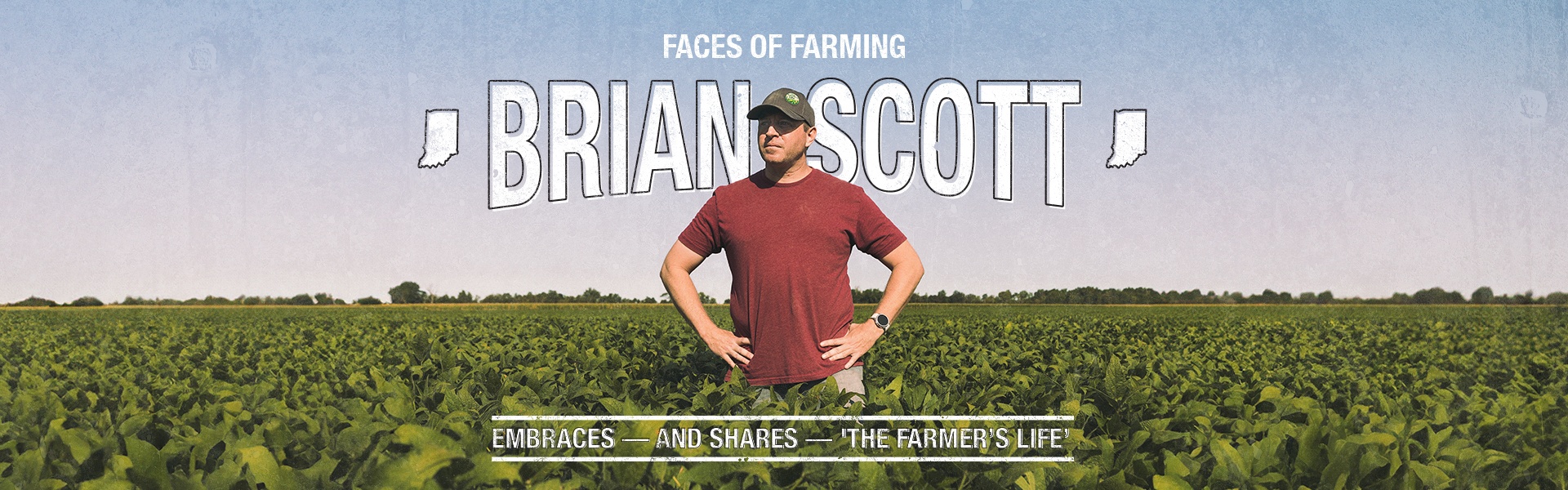

Faces of Farming: Brian Scott Embraces — and Shares — ‘The Farmer’s Life’

As a fourth-generation Indiana farmer, Scott takes a fresh approach as a grower and social media influencer.

Waxy corn provides an ingredient used in the glue that holds cardboard boxes together.

“I learned that at a contract grower meeting,” says Brian Scott, grower and social media influencer near Monticello, Indiana. “The price for waxy corn went up during the pandemic, when the demand for shipping boxes skyrocketed because so many people shopped online.”

Waxy corn is a specialty crop that looks the same as yellow field corn, but its starch content makes it ideal for a variety of industrial and food uses.

Scott and his dad devote about half of their corn acres to waxy hybrids and half to regular field corn. They also grow a couple hundred acres of popcorn, soybeans for seed production and a few acres of winter wheat.

While their fields look like others in northwest Indiana, their crop mix doesn’t quite fit in with the idea of a typical Midwest farm. Scott took an alternative approach to becoming the fourth generation to work the family farm as well.

Taking a Detour From Farm Life

“I wanted to farm as a kid,” Scott says. “It’s what I knew. I never did anything else.” Yet, in high school, he describes himself as “not a typical farm kid.”

“I wasn’t involved in FFA or 4-H,” he explains. “I played trumpet in jazz band and took music theory, so I didn’t have room in my schedule for ag classes. Most of my friends were town kids, and I didn’t rush home to drive the tractor after school or come home from college to farm.”

Yet he majored in soil and crop management at Purdue University with the intention of returning to the farm immediately after graduation, like his dad had done in the 1970s.

“I didn’t have another plan, until I wondered during my last semester of college if I should do something else,” he says.

Scott wanted to forge his own post-college path, so he took a job outside of agriculture as an assistant manager at a farm and home retail store in his hometown. He was promoted to store manager, and then the chain moved him to manage a new store in a nearby town.

He learned to be outgoing and how to work with many different people. He served customers, oversaw 30 to 35 employees, and answered to upper management.

After six years in retail, Scott began to tire of the long hours in town and the need to be available during his limited time off. He spent a few years looking for the right position close to agriculture before deciding to join his dad and grandpa on the family farm. He says they made it easy for him to seamlessly join the operation, and they were excited to introduce the next generation to the farm. Only two days after quitting his retail job, Scott and his wife, Nicole, found out that Nicole was pregnant with their first son.

Their sons Matthew, 14, and Andrew, 9, show some interest in the farm as a future career. “Our plan is to be ready if they want to join the farm, but we aren’t pushing them,” Scott says.

Adapting Agronomics for a Flexible Approach

Scott isn’t afraid to try different agronomic approaches in an effort to take a calculated risk for the benefit of the operation’s bottom line.

He and his father completely transitioned to no-till on all their acres, requiring less labor. They aim to seed cover crops on about 25% of their acres each fall. And, based on research out of Purdue University, they started planting soybeans before corn.

“Soybean growth is based on day length, so planting early supports yield, especially in warm springs,” Scott says. “Though we’ve always treated bean seeds at planting, it’s even more important when planting early in no-till fields.” Scott uses Saltro® fungicide seed treatment to protect their soybeans from disease like Sudden Death Syndrome.

Because he grows soybeans for seed production, Scott can earn premiums based on quality at harvest. The seed company they grow for doesn’t require in-season fungicide treatments, but they have been rewarded in some seasons after applying Miravis® Neo fungicide to control disease and protect plant health. In winter wheat, Miravis Ace fungicide has provided similar benefits.

“This season, we are trying Miravis Neo in corn for the first time,” he says. “Our focus is tar spot, which has become a problem. It should also ward off late-season diseases and help the plants stay green longer, extending the grain fill period.”

Sharing “The Farmer’s Life”

Scott’s willingness to explore new or different tools and practices extends beyond the field. In 2011, he started a blog and joined Facebook to share his ag expertise.

“My original goal was to show people not in farming how it works,” he says. “I wanted to explain things like GMOs without a lot of jargon.”

He named the blog “The Farmer’s Life” and began sharing his thoughts and perspectives on food and farming. When Scott worked in retail, he helped many non-farm people understand things like garden chemicals, so he had experience relating to his audience.

“When people learn that I’m a farmer, they tend to ask questions,” Scott notes. “This was a way to answer those questions for more people.”

My original goal was to show people not in farming how it works. When people learn that I’m a farmer, they tend to ask questions. This was a way to answer those questions for more people.

He became part of the online ag advocate community. Over the past 13 years, “The Farmer’s Life” has evolved with online platforms. He moved away from the blog format and writing about food issues and now uses social media channels to share everyday life on a crop farm.

“I still target the non-farm audience, but I know that posting equipment and farm pictures attracts those who grew up in agriculture but aren’t farming, as well as other farmers,” he says.

He typically posts once or twice a day on Facebook, where he reaches his largest audience of more than 151,000 followers. He shares almost as often on Instagram, where he connects with a mix of farmers and others. When he has questions for other farmers or something more sarcastic or funny to share, he goes to X, formerly known as Twitter.

The Farmer’s Life also has a YouTube channel, where Scott shares longer videos about his life on the farm. He even had a viral TikTok video on the differences between sweet corn, field corn, popcorn and waxy corn, which earned six million views.

Engaging online has expanded his network of farmer friends. “I don’t drink coffee, so I don’t go to a coffee shop,” Scott says. “Instead, I have close friends from around the country that I private message or text.”

From consumer retail to waxy corn, Scott’s approach continues to be unique. But that experience fuels the success of “The Farmer’s Life” — and his satisfaction as a fourth-generation farmer.

5 Min Read

- Brian Scott’s career detours and life on the family farm equip him to share about the life of a farmer.

- A willingness to try new practices, technologies and products characterizes his approach to farming and more.

- He documents the everyday ups and downs of farming on multiple social media, platforms, including Instagram @TheFarmersLife.

More Articles About Community & Culture

5 Min Read