How to Identify Corn and Soybean Weeds

Identifying troublesome weeds is the first step toward protecting corn and soybean yields from thieves like waterhemp and Palmer amaranth.

Weeds represent a significant economic threat to growers across the country. Identifying weeds and remaining vigilant through regular scouting is critical to formulating a proper plan. Uncontrolled or mismanaged weeds can damage crops, compete for resources, contribute to herbicide resistance and slow harvest. According to Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, incorrectly identifying problem weeds can mean the difference between profit and loss.

Waterhemp vs. Palmer Amaranth

Palmer amaranth and waterhemp are two of the most widespread and devastating yield-robbers growers face, with populations in almost every corn- and soybean-growing region in the U.S. To make matters worse, the International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database Weed Science map shows that populations of both weeds exhibit herbicide resistance.

These pigweeds are frequently misidentified, but a few key characteristics help set them apart.

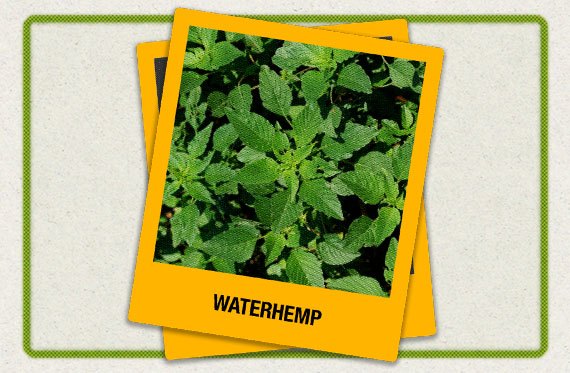

Waterhemp

An AgWeb poll asked about 400 growers what their “top weed nemesis” was. Unsurprisingly, waterhemp took the top spot, earning 35% of the votes.

Waterhemp is a small-seeded broadleaf weed that compensates for its tiny seed size with a fast growth rate. Its lightweight seeds thrive in minimum and no-till situations, where they germinate quickly near the soil surface or in crop residue. Plants generally produce about 250,000 seeds per plant, although some can produce as many as one million seeds, making them a prolific and costly problem for growers.

Waterhemp emerges throughout the growing season, but a higher percentage appears later than most annual summer weeds. This allows waterhemp to escape many preemergence herbicide applications and persist after post-emergence applications, especially those with no residual, like glyphosate, or limited residual. Waterhemp plants that are left to go to seed can quickly populate the soil seed bank with millions of seedlings, increasing resistance and ensuring costly management issues for years to come.

Look for:

- Waxy, oar-shaped seedling leaves.

- Hairless stems that range from green to red-pink in color.

- Glossy alternate true leaves that are oval or lanceolate in shape.

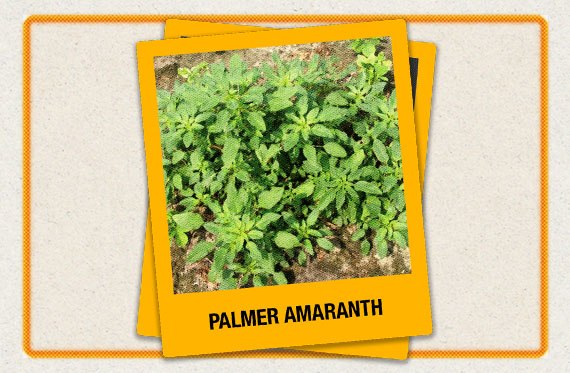

Palmer Amaranth

Another broadleaf weed, Palmer amaranth shares many characteristics with waterhemp. Its small seeds thrive in minimum tillage fields. Plants can produce at least 100,000 seeds when in competition with a crop and almost 500,000 seeds in non-competitive scenarios. If escaped weeds get the chance to produce seed, they can cause serious consequences for future seasons. Like waterhemp, Palmer amaranth persists after non-residual or limited residual herbicide applications. Palmer amaranth has been steadily spreading northward in recent years and continues to raise alarms for herbicide resistance.

Palmar amaranth’s emergence period extends well into the growing season. Out of the many tough weeds growers need to scout for, Palmer amaranth may be the most unpredictable. Start scouting early and continue throughout the growing season to stay in control.

Look for:

- Oval- or diamond-shaped seedling leaves.

- Alternate true leaves that are alternate and lanceolate in shape.

- Smooth and hairless stems.

- Seed heads that grow up to 30 inches long.

- A single hair at the leaf notch of the first few true leaves can sometimes, but not always, distinguish Palmer amaranth from waterhemp.

Even experienced growers may still confuse these two weeds. When in doubt, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln recommends a few tips to help growers tell the difference between waterhemp and Palmer amaranth:

- Palmer amaranth cotyledons tend to be longer and narrower compared to waterhemp cotyledons.

- True leaves on Palmer amaranth may be notched at the tip; hairs are less common on waterhemp seedlings.

- If the petiole is shorter than the leaf blade, the weed is probably waterhemp. Palmer amaranth, on the other hand, has petioles that are as long as or longer than the leaf blade.

Proper identification is more difficult after the flowering stage, so don’t let weeds mature before scouting.

How to Identify Common Weeds

Although waterhemp and Palmer amaranth dominate headlines across the Midwest and Central Plains, there are plenty of other tough weeds that should be on your radar.

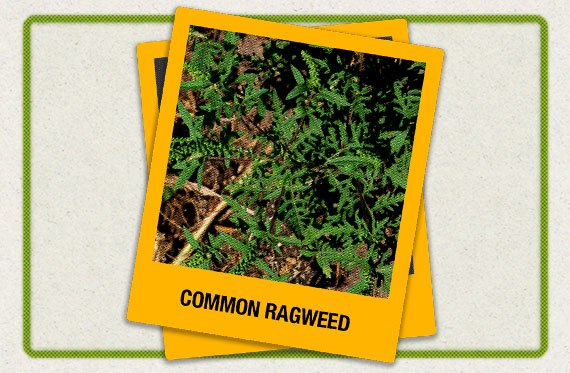

Common Ragweed

Common ragweed is an aggressive broadleaf weed from the aster family. According to Michigan State University, one common ragweed plant per 10 square feet can cause a 30% yield reduction in soybeans and average 3,500 seeds per plant.

Look for:

- Common ragweed grows to 1-3 feet in height.

- Purple seedling stems and dark green, paddle-shaped cotyledons.

- Green leaves that are deeply divided into lobes.

- Branched and hairy stems.

- Fern-like leaves 2-4 inches in length with longer stalks on lower parts of the plant.

- Clusters of green male and female flowers.

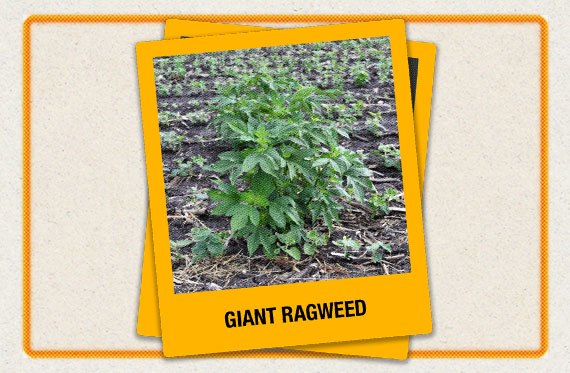

Giant Ragweed

Another aster, this large-seeded broadleaf can reach heights of up to 20 feet and has a big appetite for your crop’s resources. Giant ragweed typically emerges several weeks prior to corn and soybean planting. It is especially difficult to control because giant ragweed seeds germinate deep within the soil profile.

Look for:

- Thick, fleshy cotyledons.

- Heavily lobed leaves that are rough to the touch.

- Opposite leaf arrangement as the plant develops.

- Weed height that is 1-5 feet taller than the crop with which it is competing.

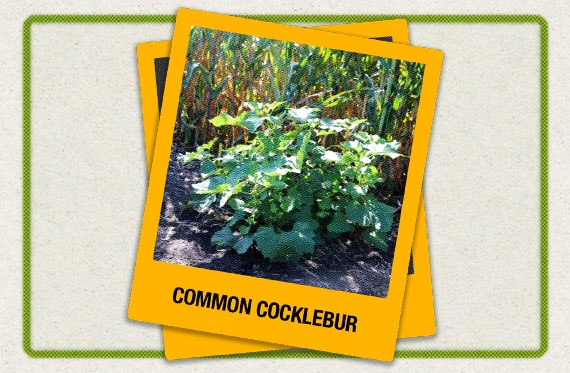

Common Cocklebur

At the seedling stage, this weed is easily confused with giant ragweed because the long cotyledons of the two species look similar. However, common cocklebur emerges closer to the end of planting. Cocklebur’s large leaves intercept a lot of sunlight, making it a highly competitive yield reducer.

Look for:

- Triangular or oval leaves that are approximately 2-6 inches in length.

- Stiff hairs on the surface areas of the leaves.

- Three veins extending from the same point on the upper side of the leaf.

- Long petioles.

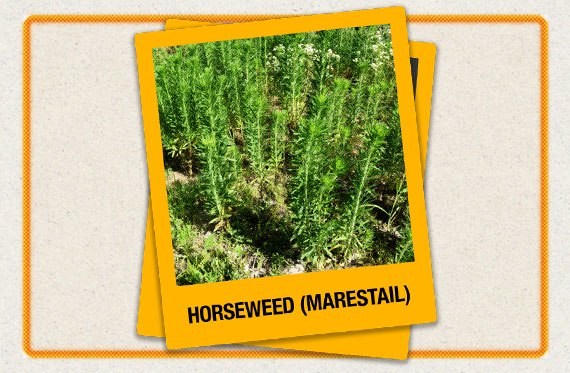

Horseweed (Marestail)

While this weed may germinate year-round in different geographies, it typically is seen in late summer or fall, and in early spring. Knocking out this weed before its highly mobile seeds spread throughout fields offers the best chance of control.

Look for:

- A basal rosette with oval to egg-shaped leaves soon after emergence.

- Alternate true leaves that are hairy and irregularly toothed.

- Leaves that decrease in size toward the top of the plant in a sessile leaf pattern.

- Growth up to 6 feet tall.

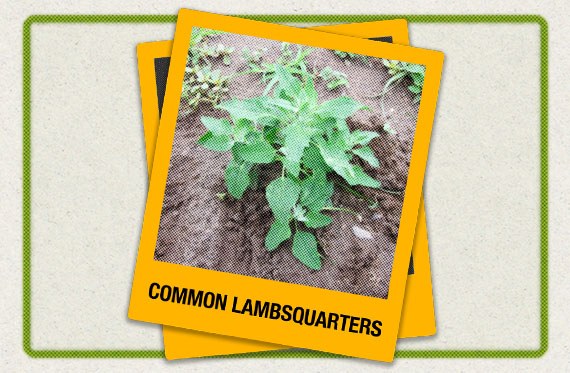

Common Lambsquarters

This early-emerging weed is one of the most competitive species, particularly due to its rapid growth rate. Each plant produces an average of 72,500 seeds, which are some of the most resilient in the soil seed bank.

Look for:

- Veinless seedling leaves that are opposite and narrow with rounded tips.

- Triangular, alternate and dull green true leaves with undulate to toothed margins.

- A mealy white coating on leaf surfaces.

- Small green flower clusters at the tips of the main stem.

How to Contain Weeds

Although a handful of weed escapes may not be enough to steal away your yields, the presence of just one weed opens the door for hundreds or thousands more next season.

The first step to manage weed escapes is proper identification. While many herbicides are labeled for a variety of common weeds, knowing exactly what’s in your field informs more efficient and effective programs. Herbicide programs with multiple effective sites of action, strong overlapping residuals and full use rates will result in the most complete control of labeled weeds.

For soybeans, start with a strong preemergent herbicide, such as Tendovo® followed by a post-emergence herbicide option like Dual Magnum® or Flexstar® GT 3.5 for overlapping residual control and resistance management.

For corn, start with a strong preemergence herbicide application of Storen®, Acuron® or Acuron Flexi. Either can be applied in one pass or in a two-pass program with a foundation rate preemergence followed by the remaining rate post-emergence. Additionally, Acuron GT herbicide is a post-emergence option that delivers fast knockdown and enhanced control of difficult weeds like waterhemp. It can be applied as part of a two-pass program following an application of Lexar® EZ or Lumax® EZ herbicides. All these solutions include multiple sites of action for resistance management and offer application flexibility.

Talk to your local Syngenta retailer or sales representative to plan a program tailored to tough and resistant weeds in your fields.

If timing doesn’t allow for herbicide applications, control escapes with methods like cultivation or hand-pulling. If pulled weeds have flowers or seed heads, make sure they are bagged, removed from the field and destroyed to make sure there is no chance of spread to your fields or your neighbor’s. Properly identifying and removing just one waterhemp or Palmer amaranth plant can mean the difference between a clean start to the next season and hundreds of thousands of emerging weeds.

Harvest Corn and Soybeans, Not Weeds

After a season of hard work, getting every possible bushel out of your acres is key. If you see weeds in your fields at harvest, consider some of these harvesting tips outlined by the United States Department of Agriculture:

- Avoid harvesting corn and soybeans located in areas densely populated with weeds — the risk of spreading weed seed is likely not worth the bushels you might get from that field.

- Adjust your combine’s cutting height settings to minimize the amount of weed seed that is harvested. Consulting with your combine provider helps determine the right height for your field conditions.

- Regularly clean your farm equipment between harvesting different fields to avoid contamination from weed seed.

- Destroy all weed seed left in the field after harvest to prevent it from entering the soil seed bank. Burning weed seed is a common method to get rid of it.

- Before taking your harvest to the elevator, be sure to examine corn and soybeans for weed seed upon arrival and to separate weed seed through mechanical cleaning or other means.

- An application of a harvest aid like Gramoxone® SL 3.0 herbicide can help keep the combine running smoothly by eliminating remaining weeds in soybean fields.

Taking these actions to minimize contamination from weed seed will help ensure your hard work pays off and will help prevent weeds from growing on your farm in the future.

9 Min Read

- The foundation of successful weed management is vigilance and proper identification. Growers can follow a similar process to identify common wheat weeds.

- Waterhemp and Palmer amaranth are two pigweeds with a knack for stealing yields and tricking growers.

- Containing weed escapes can prevent hundreds of thousands of yield-robbing seeds from entering the soil seed bank.

More Articles About Field Insights

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

9 Min Read