As you plan for next season, don’t overlook early-season diseases like Phytophthora. In 2021, 36 University Extension Plant Pathologists estimated an annual average of over 25 million bushels of soybean yield loss due to the disease1. This year, MN, OH, IA and other states reported high Phytophthora pressure, which could increase the risk of infection next year.

Phytophthora is one of the most destructive early-season pathogens and significantly limits plant stand establishment in soybeans. It not only reduces potential yield by killing seedlings and reducing the root efficiency of mature plants, but it can infect plants at any time during the planting and maturing stages, if the conditions are right.

Here are some tips to help you protect your soybean crops from heavy Phytophthora pressure:

- Be aware: Knowing what to look for can help you minimize the damage Phytophthora causes in soybean fields. The University of Minnesota Extension recommends looking for symptoms at each season stage since the infection can occur from the beginning to the end of the growing season.

- Early-season: Infected seedlings and plants will have stems that will likely appear bruised with yellowing leaves.

- Mid-to-late season: Brown lesions may start to appear on the roots as they begin to rot. Leaves will continue to yellow and wilt, staying attached to the plant even after it begins to die.

- Incorporate Phytophthora-resistant varieties: Planting Phytophthora-resistant varieties will set the foundation for managing the disease and protecting your soybean yield.

- Review your field history: Relying on the historical data of your fields can significantly help you prepare for the yearly threats you face.

- Use a robust seed treatment: Selecting a seed treatment that contains effective modes of action against Phytophthora and allows the establishment of seedlings and inherent native gene resistance will protect your investment.

CruiserMaxx® APX seed treatment protects against Phytophthora and other early-season insects and diseases, like Pythium. It has two highly effective Phytophthora protection active ingredients and combines proven protection with picarbutrazox (PCBX), a powerful Pythium and Phytophthora-fighting molecule.

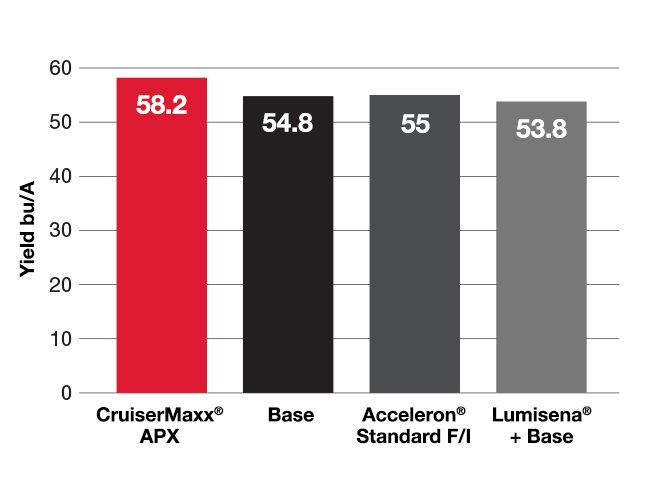

In an Ohio State University Phytophthora trial, CruiserMaxx APX was the only seed treatment to deliver a statistically different five-bushel yield advantage compared to the check treatment; the competitors included Lumisena™ and ethaboxam compounds, which did NOT beat the untreated check2.

For more information about the advantages of CruiserMaxx APX seed treatment, reach out to your local Syngenta representative.

1 Plant Health Progress 2021 Vol. 22 No.4 pp. 483-495

2 2018 Ohio State University Phytophthora trial; α = 0.05