Know which early-season diseases to look for and create a careful scouting plan to confirm them and assist you in managing them long-term. Red crown rot (RCR) is becoming a more common early-season soybean disease that is tough to diagnose because it’s often mistaken for other diseases, like Sudden Death Syndrome (SDS) or brown stem rot. Learning how to tell if you’re dealing with RCR will help you manage your crop and set you up to preserve your soybean yield.

Understanding Red Crown Rot

Caused by the soilborne fungus Calonectria ilicicola, RCR historically was a Southern disease threat, but it was first confirmed in Illinois in 2018. Since then, it has been found in more counties in southern Illinois, western Kentucky, southern Indiana and a few counties in Missouri.

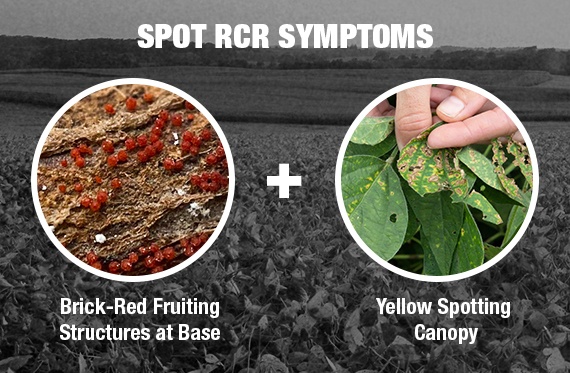

One of the most distinctive signs of an RCR infection is brick red fruiting structures at the base of the soybean plant; but unfortunately these reproductive structures are not always visible. RCR also causes yellow-speckled spots on leaves in the canopy. Because it’s a soilborne disease, farm machinery and tillage can move the disease from field to field if the machinery isn’t properly cleaned in between uses. The pathogen can easily move from an infected field to an uninfected field.

“Red crown rot devastates yield by destroying the root system until there’s just nothing left,” says Dale Ireland, Ph.D., Syngenta technical product lead. “RCR absolutely destroys the root system’s ability to uptake moisture and nutrients. There’s next to no yield in those early infected plants.”

Red crown rot absolutely destroys the root system’s ability to uptake moisture and nutrients. There’s next to no yield in early infected plants.

The symptoms of RCR often resemble those of SDS, which is caused by a different pathogen – Fusarium virguliforme. “We believe that RCR may be more widespread than what people realize, since its presentation of yellow-speckled spots on the leaves are currently primarily associated with SDS,” says Ireland.

Another similarity between SDS and RCR is that soybean cyst nematodes (SCN) can exacerbate infections from both diseases. SCN also destroys the crop’s root system, opening the root system and creating more opportunity for either RCR or SDS to infect the roots.

If you suspect RCR, collect a sample and send to your local state Land Grant University diagnostic lab for analysis/confirmation. Don’t play plant pathologist — trust the experts at your local university.

Preserving Soybean Yield

No rescue treatments for RCR exist, but prevention and containment can help. If you suspect RCR, clean equipment thoroughly between fields or work areas with known infections last to prevent spreading the pathogen. Red crown rot thrives in temperatures between 77-86 degrees Fahrenheit so planting earlier can help prevent early infections. Another option is rotating to a non-host crop like corn and/or wheat for two years to break the RCR cycle.

One of the most effective ways to combat an RCR infection is using a seed treatment like Saltro® fungicide seed treatment, powered by ADEPIDYN® technology. Saltro has a 2(ee) label for the suppression of RCR in seven states: Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio and Tennessee.

“Saltro has direct activity against Calonectria. It’ll effectively reduce the growth of Calonectria on the developing soybean root so the plant can potentially yield more,” says Ireland.

Syngenta supports a FIFRA Section 2(ee) recommendation for Saltro for suppression of Red Crown Rot in Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio and Tennessee. Please see the Section 2(ee) recommendation to confirm that the recommendation is applicable in your state. The Section 2(ee) recommendation for Saltro should be in the possession of the user at the time of application.